The Rise of the Mini-Grid – Part 2 of 2

Tweet this: #minigrid #diesel #solar #climatechange #ruralparadigm #KUDURA #EndPoverty #EnergyPoverty #solar

Access this blog in Portuguese / Aceder esta blogue em portuguese

In part one of this series we established the need for step-change minigrid solutions to the rural paradigm and in this part we discuss the pros and cons of such solutions.

To recap the issue in part one of the blog, that solar home systems cannot scale to solve the problem of rural electrification, an interesting debate between the Sierra Club and The Breakthrough Institute highlights the topic. The Breakthrough Institute notes that solar home systems and similar devices are, “a vision of, at best, charity for the world’s poor, not the kind of economic development that results in longer lives, higher standards of living, and stronger and more inclusive socioeconomic institutions.”

To that point, the IEA estimates that in order to achieve universal access to electricity by 2030, over 40% of all installed capacity would be most economically delivered through minigrids. One particular example is a solar-biomass hybrid system where schools and small businesses can be powered during the day by a relatively small solar-PV system and, using maize cobs for example, as waste to produce energy through gasification, can in-turn power a high-load grain mill to produce flour and then packing it for transportation all while powering surrounding households and other productive energy uses during the night. As an added benefit, the by-product, biochar or charcoal, can even be used as soil fertiliser on the next maize crop or turned into briquettes for cooking, augmenting further the businesses’ revenues or the schools’ savings from a carbon-neutral energy source.

Another benefit is as power needs increase over time, flat or energy-based tariffs can be adjusted accordingly without retrofitting the system’s capacity or jeopardising the minigrid’s stability in a reliable, leveraging and affordable fashion. In fact, Pike Research is predicting a 21% increase in capacity for the remote minigrid market by 2017, from 349 MW to 1.1 GW.

Perhaps the main hindrance to mainstream adoption of minigrid energy solutions as of yet is the PERCEIVED high initial capital cost required. Along those lines, another potential obstacle is the lack of funding for minigrid solutions, both of these obstacles are great topics for a future blog series don’t you think? J

The rural paradigm in Africa is very clear – millions of people today still do not have access to modern energy services, safe drinking water and proper sanitation facilities which is causing millions of human deaths annually, a continuous cycle of poverty along with serious environmental depletion.

Every case has its own inherent variables and the “best” solution needs to attain those same variables in an effective, optimised and efficient way. Small-scale, solar-based systems certainly play an important role in lighting and some electricity needs – the IEA estimates that systems like these will account for 20% of new electricity needed by 2030 – but inherent limitations can make them only an interim or, to some extent, a leveraging solution for most cases.

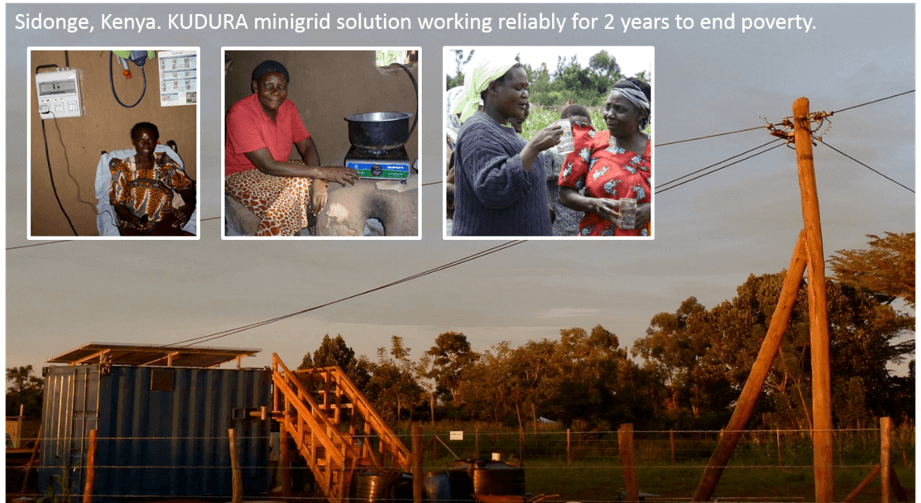

Minigrids on the other hand offer a scalable solution for entire communities, schools, businesses (i.e. farms, factories) and clinics where renewable energy uses AND drinking water services can drive rural communities out of the rural paradigm by generating wealth from within and outward, empowering local populations to achieve a self-sustainable, self-running, clean energy model for years to come, even if the national grid never comes – in line with our minigrid solution KUDURA, aptly meaning “the power to change”.